Reading is an unnatural act. Unlike the appreciation of aural and visual arts, reading requires conscious effort even before deep interpretations are sought. Children see, smell, touch, hear, and learn to speak, before they master the written word. It’s the hardest form of basic communication. Harder still if it courts the edge of the expected by riding upside down on the underbelly of unnatural beings while holding onto its senses by the seams of its straightjacket. Hardest of all, possibly, if it’s …

… surrealism.

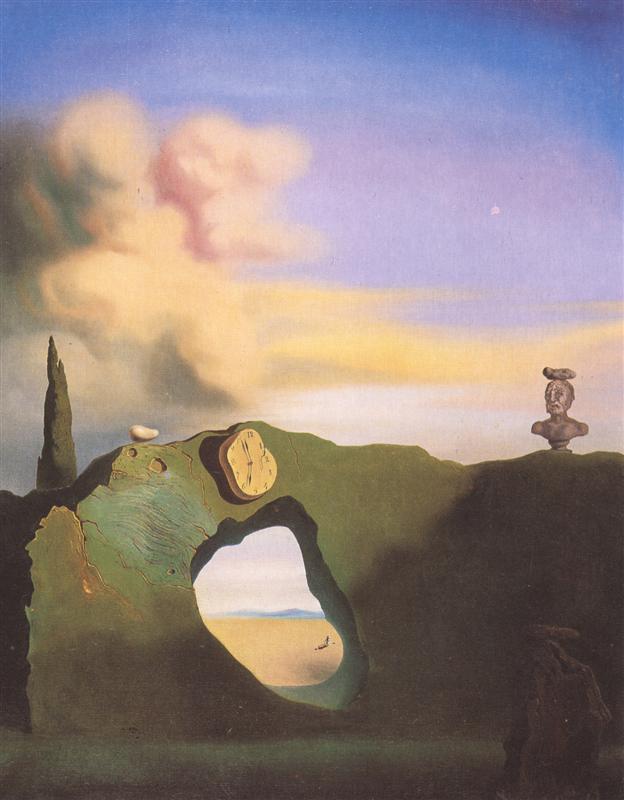

Dali flashes before the mind. But, that’s not what I mean: the visual mind sees, then interprets or doesn’t. Reading surrealist literature, however, is an act of spike-studded iron will (and no little amount of curiosity for the quaint that you hope no one else ever finds out about).

Forget drinking from a firehose—firehoses gush at you, and it’s just water. Think instead: a fountain spouting body parts, balloons, beetles, bronze tables and acid blue jackets floating between the blessings and the bronchitis, and you roll up your trousers, step over the rim into this bizarre potpourri, get dragged down by something slithering in the water, but continue sitting in there with water up to your chin, collecting random floating objects and putting them together like legos—creating your very own Frankenstein. Occasionally you pluck up a memory or a scar. Occasionally you cut yourself.

Who said that exploring the unexplored within the safety of a book was good practice?

I’m not trying to be off-putting.

Actually, I am: if you’re not the kind to throw yourself into the aforementioned fountain out of curiosity (or spite, or kink, or whichever particular personal quirk), I would recommend fishing out only choice morsels and grappling with them on dry land.

You might discover you’re developing some odd tastes.

Today’s rather tame Quote comes from The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington. She died in 2011 at the age of 94, and was one of the last surviving participants in the Surrealist movement of the 1930s. This is how she opens her short story called The Royal Summons.

Quote:

I had received a royal summons to pay a call on the sovereigns of my country.

The invitation was made of lace, framing embossed letters of gold. There were also roses and swallows.

I went to fetch my car, but my chauffeur, who has no practical sense at all, had just buried it.

“I did it to grow mushrooms,” he told me. “There’s no better way of growing mushrooms.”

“Brady,” I said to him, “You’re a complete idiot. You have ruined my car.”

So, since my car was indeed completely out of action, I was obliged to hire a horse and a cart.(Translated from the French by Kathrine Talbot with Marina Warner)

According to the information you have, where is the car? Take a guess.

What makes the Quote quiver?

The bizarre.

My best guess is that the car is two feet underground, sporting rootlets, rabbit burrows, and a novel type of ferrous-flavoured auto-truffle.

In other words, my guess is as good as yours.

The plain delivery of the dialogue, the matter-of-fact explanation of the car’s absence, the justification, and the protagonist’s acceptance of said fact as truthful (my chauffeur has no practical sense, I was obliged to hire a horse and cart) all imply the same thing—it’s much easier to take the Quote at face-value then trying to pin some deep interpretation onto it.

Or is it?

You’re free to hold the Quote as a question mark in memory and proceed through the story looking for a constellation of signs, looking for meaning. But …

… there are too many such question marks to bear in mind, so after a while you take what is being said literally and think of yourself as a peripatetic in a mini picaresque story, where every paragraph, sometimes every phrase is a new image, a new idea, a new place.

I wrote that Anne Carson made the bizarre beautiful and meaningful in verse-novel Red Doc>. But even through the distorting veil of a poetic license, her work is not raw and uncensored on a micro level—anything but: it’s compact, smooth, and polished, like a cabochon. You learn to expect elegance after ever line break.

In surrealism you learn to expect a random word generator and are surprised it’s not as bad as that.

What is at the core of the Quote?

Metaphorical itch.

The Quote smells of metaphor to me. But try as I might I make nothing of it. Worse, I tell myself there are no metaphors in surrealism, not the way you’d expect, and then I stumble at the first next incongruous statement. It’s like an itch I’ll never be able to scratch, but I keep trying anyway. A few more direct quotes from the same story:

- The queen was in her bath when I went in; I noticed that she was bathing in goat’s milk. “Come on in,” she said. “You see I use only live sponges. It’s healthier.” The sponges were swimming about all over the place in the milk, and she had trouble catching them.

- The queen called me to her office. She was watering the flowers woven in the carpet.

- “Head colds are easily cured, if one just had the confidence,” the queen said. “I myself always take beef morsels marinated in olive oil. I put them in my nose.”

- “But bronchitis is more complicated. I nearly saved my poor husband from his last attack of bronchitis by knitting him a waistcoat.”

Have you visualised all of that?

In his essay Metaphor, philosopher of language John R. Searle analyses how we extract metaphors from a given statement. (One source for the essay is Metaphor and Thought, edited by Andrew Ortony.)

For a metaphor to work, the reader must first detect its presence, and in particular, note that a literal interpretation is inappropriate. For example, saying, Charming, that’s just what I needed now, moments after your wallet was stolen, or, He’s an animal when he’s drunk, are probably not meant to be taken literally.

But may I ask the obverse question: what is needed for an utterance to be interpreted literally?

Ideally, it ought not to trigger the search for a metaphor: it has to make sense in its obvious form. Alternatively, it’s like the Quote: it triggers the search, but there’s no suitable metaphorical explanation.

Searle provides a neat diagram delineating basic ways to interpret an utterance (I paraphrase, and give my own examples in italics):

- Literal interpretation (it is what it is): The sky is blue.

- Metaphor (the meaning is deeper): The sky is an ocean.

- Irony (the meaning is opposite to the statement): Yup, the sky is definitely blue!, when you’re caught in a thunderstorm, after the weather forecasts said blue skies.

- Dead metaphor (meaning has shifted over time): He is blue, when you’re looking at the guy and he doesn’t have blue face-paint on, rather, he’s sad.

- Indirect speech act (meaning is both literal, and deeper): At least you can see a patch of blue sky from your cell, used to say both you can physically eyeball it, and it gives you a view into freedom.

I would suggest that an honorary member is missing from the list:

- Metaphorical itch (meaning is literal, even though it feels it ought to be metaphorical): I tied the car to a weather balloon and sent it into the blue sky. I did it to seed rain clouds. There’s no better way to seed rain clouds.

And oh look, it’s raining!

(How can anybody be a person of quality if they wash away their ghosts with common sense?

—Leonora Carrington, Waiting)

I need to scour your site at leisure so that I can learn more on experimental writing….you really write well….I have lots to learn

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kind of you to say so! Questions, comments, suggestions—do let me know, they’re always welcome 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I have many, will definitely seek your advice on my next write up. Thank you so much 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good luck and see you around! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes please. Here is the link to my poem (experimental writing). Do let me know, how I can improve?

https://solitarysoulwithachaoticmind.wordpress.com/2018/01/04/unfinished/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sending me your poem! I hope you’ll find something useful in what I wrote back 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am grateful that you genuinely took interest in my poem and took out the time to read it in detail….your tips are invaluable….gonna use them on my next experimental writing piece 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool! Well let me know if you ever have any questions or comments on my articles—will be glad to answer them 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sure 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interpretation is a two way street. And it depends on age and circumstance.

I’m feeling blue because I am 17 and in love

I’m blue because I just lost a boxing bout and am bruised all over

I’m blue because I’m old and am having a heart attack.

et etc et cetera

And while I was reading the idea of interpretation morphed into translation so I played a little game with translations.

I have Italian Danish German blogger friends and I have to get Google to translate and then they have to translate my comments back again. So here goes

English version of Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Sent via Danish and back to English

Do not go carefully into the good night,

Aging should burn and rave near the day;

Rage, rages against the death of light.

Although wise men know at their end that dark is right,

Because their words had not smiled, they were lightning

Do not be careful about the good evening.

It makes sense of the quote “Loses something in the translation”

LikeLiked by 2 people

At a scientific level, I agree, no two interpretations are the same. Indeed, as we discussed “All novels are translations, even in their original languages”, and that applies on all levels across all people and time. I also agree that something is lost in the translation (although I am still sceptical of machine based-translation for everything but the most basic informational purposes), however, something too may be gained. I believe that since last year the Mann Booker Prize money for translated novels is split evenly between author and translator. An interesting proposition. Without the author there would be no translation, but without the translator the novel would not be accessible to some portion of the humans. So is 50-50 a good split?

On a separate note, just today I was reviewing Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (which prompted our previous related discussion, and to which I linked above). I still maintain the Michael Cunningham introduction was almost as worthy of my time as Mann’s novel. Here Cunningham talks about the particulars of the Henry Heim translation:

And indeed, upon closer inspection the Heim translation is a veritable artwork in itself. So on the one hand translators are necessary, but on the other they can give a work a new lease of life, transforming it, modernising it, sculpting it. Perhaps we should consider (good) translators not as a necessary evil of post-Babel times, but as artists in their own right, writers who create meta-art that most of us never appreciate for the “meta” part, but only for the “art” part.

LikeLike

So imagine I am telling you that a particular line in a poem means such and such and then the author stands up un-be-known to me and says he meant something else. Does that mean I am wrong? I’ll write a post tomorrow. about such a thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That old chestnut? That issue harks back to the whole “is the author allowed to claim there is a unique interpretation of their work” or “is the work untrammelled the moment it’s let out into the world to gain a life of its own”?

I’d say the latter is true, but the former too: the author can stand by their intended meaning, by what they wanted to say, but the work also has to stand on its own (it shouldn’t need the author to hold its hand). Of course cross-pollination of ideas goes both ways, but fundamentally—to answer your question—you’re both right. Or should I say, neither of your is wrong?

LikeLiked by 1 person

P.S. I look forward to hearing your take on it!

LikeLike

You might enjoy reading Robert Okaji’s poetry translations. He works from Google’s manglings and out of them manages to pull some really beautiful poetry. https://robertokaji.com/2017/09/27/laolao-ting-pavilion-after-li-po-2/.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! That’s an interesting concept–just checked it out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Ellen, Thanks for the suggestion. I did follow Robert for quite some time but I stopped. Not because I didn’t like his work but because it was a one way street. I live on my own and I enjoy the back and forth of comments, banter and discussion that comes with following and being followed. I may dip into him again from time to time. However I must say I enjoyed dipping my toe into your blog. As an Australian I am always intrigued by an American’s look at Britain, Great or not.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s interesting you should put it that way. I’ve noticed some blogs have a like-for-like policy: if you like/comment on their post, they will almost without fail like/comment on yours (but not otherwise). Which brings me to the question: if people like your blog and comment, do you have an obligation to do the same for them? What if their content simply isn’t something you can relate to or interact with easily? This is rather touchy subject, so feel free not to answer.

Life is busy sometimes, and it’s hard to always keep up with fellow bloggers. But I hope that through my posts—through the (let’s suppose) decent quality of my content and the time invested to create it—my readers know I appreciate their attention and I do my best to entertain them.

LikeLike

‘m not sure I am completely “Like-for-like” but I do certainly prefer to have a conversation. Some blogs more than others. In the case of A Quiver of Quotes I would enjoy reading the post even of there was no ‘comment’ box but I would never be as intrigued by it.

LikeLike

Oh I prefer a conversation too! Thanks for sticking around and bouncing ideas off my posts—much appreciated and lots of fun.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved your introductory paragraph. I’d never thought of reading as being a difficult act, but your hook paragraph had me thinking….and reading is definitely difficult, not natural. We can look at a painting by a Chinese artist, but to read the paintings title written in Chinese underneath would be beyond most people reading this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How pertinent! I was just looking at a painting by a Chinese artists and had the same experience … In the context of books, I meant more that an active effort is required to trammel our attention to the lines on the page and squeeze meaning out of them—but your point is even more universal.

Thanks for letting me know which bit you enjoyed 🙂

LikeLike

On a physical level, is the writing itself not a metaphor? I mean without even writing metaphorically, the symbols are themselves metaphors. Interesting that you say reading is an unnatural act, but not that writing is……

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re write, fundamentally all communication is symbolic (a mapping from one domain of meaning to another), although some are more universal and conventional than others.

As for writing, I hadn’t gotten that far 🙂 Developmentally, writing comes after reading, so in some sense it can’t be all that natural (although of course, someone had to write something down first, for it to be read). That said, the desire to express ourselves, once we’re familiar with the mechanics of writing, may be so strong—and possibly much stronger than our desire to read—that it’s almost natural (just an off the cuff remark). I’m curious what you think?

LikeLike

Some desire to express more, others to get lost in reading (my other half is a bookaholic). I think the key to both is that we get lost in dreams – daydreams. The writer in their own which they write down, and the reader in others dreams, which they pick up. Maybe that’s not a particularly coherent answer to the question.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well put! (Sorry this comment got lost for a while.)

I think the key to both is that we get lost in dreams – daydreams.

That’s a neat way to think about it. Readers describe the phenomenon all the time (because there are more of them?), but I agree with you, writing too is about getting lots in the creative daydream. Especially with larger pieces of fiction/fantasy, which require not only plot development, but also extensive world building: coming up with a coherent structure for both elements requires an ability to guide the daydream in different ways until the most satisfactory shape is achieved. It’s both a struggle and a pleasure. And it’s one of the most immersive activities I know (possibly because it allows anyone to act at the maximum of their creative capacity, and experience flow—but that’s a theory for another day).

Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

LikeLiked by 1 person